I’m working on a show right now that has no sound designer.

In fact, it doesn’t have much design at all. The company decided to cut corners on the cost of designers, and we ended up with only two, splitting all of the various departments (lighting, video projections, costumes, props, and set) between them. Sound got left out, somehow. The director provided mp3s for a few specific moments in the show, and then was surprised when they sounded compressed-to-hell played over the big sound system (’cause an ipod with cheap earbuds doesn’t give enough depth of sound for you to tell that this music sounds like hissy, flattened crap). But at least, for all that the costumes got delivered last minute and don’t all fit, for all that there are parts of the set that never got painted, for all that the lighting look for the show is too damn dark, there’s at least someone who’s supposed to be responsible for it.

The sound of this show was cruelly orphaned, and the absence of a carefully curated soundtrack is like an anchor tied around the show’s skinny neck, dragging it down and making it impossible for it to fly. As a mere hired technician, brought in during the final few days before opening just to press buttons and do what the company says, I sit there listening, every time, for something that isn’t there. Something that can’t be there, because no one conceived of its necessity. It’s a problem I can’t fix, because it’s not my job, but it’s no one’s job, and that’s devastating.

I can’t even count how many times I’ve been in early-planning meetings and someone — a director, perhaps, or a producer; someone who doesn’t design and doesn’t know how to — says the fateful words, “I’m not really sure if we need a designer for this”. Whatever department they’re talking about, it’s a moment when every technician and designer cringes.

“But there’s only one sound mentioned in the script; I’m sure someone can find us a telephone ring”.

“But I already know what I want for the set; we can just bring my couch from home”.

“We really only need two lighting washes, and our stage manager knows how to run a lighting board”.

“The actors can just bring their own clothes from home, and we’ll pick out their costumes from that. If anything’s missing we’ll go to Value Village”.

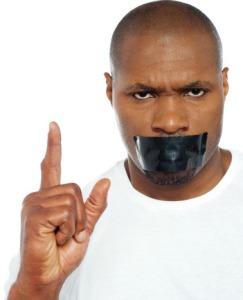

It is at this point when any designer, technician, technical director, production manager, or literally any sane person in the room should say “NO!” Say it quickly, before anyone can even begin to consider this horrible idea of not having designers for every department. Say it loudly, and in a tone of horror, because no one should ever be considering giving in to this temptation to attempt to do it themselves.

I promise you, the audience WILL know the difference. They might not know exactly what was wrong with the show — might not be able to put their finger on that feeling of unease — but they’ll feel it. Deep down they will sense that there’s something wrong with this show; something incomplete, perhaps. Something amateurish. Something that could have been better, but then wasn’t; like a parade that happened two streets over while you waited for it to pass at the wrong intersection.

In the case of the particular show that I’m working on, the director wanted lots of silence. The show is Modern, surreal, industrial, and bleak: there are long, pregnant pauses and strange moments of dark emptiness. But silence, in a theatre, isn’t truly silent. Having nothing is distracting; it feels incomplete. Much like an “empty” stage still has its architectural structure, its walls, its black curtains concealing the backstage, and the line dividing audience and actors (sometimes deliberately crossed, but always, unremittingly present), stage-silence isn’t, truly, silent. The audience rustles, coughs, and breathes. A set piece squeaks as it’s moved into place. The lighting instruments whir and hum, and the lighting board clicks as the technician presses “GO”. Actors’ footsteps tap across the stage floor and doors are opened and closed in distant, backstage hallways. Cars go by on the street outside and the wind moves its way around the building, rattling shutters and whistling through gaps.

Like the architecture that surrounds the stage, the edges of the beams of light, the black curtains that conceal the stage doors, or a coat of paint that makes a plywood table look mahogany, a good sound design wraps the space of the play in a barely-perceptible blanket, muffling reality and subtly shaping the world in which the audience’s disbelief is suspended. A proper “silence” forms the background noise that gives any space its texture; the white noise that underscores every place and time with its constant, barely-noticeable presence. The dream in the forest is gently supported by the sound of wind, rustling through high-up leaves. The tower is made darker by the hollow, echoing sound of its stones. The mysterious cave reminds you of its proximity to the sea by the distant crashing of waves at its entrance. The solicitor’s office contains the rustling of paper and the distant clicking of typewriter keys, or the murmur of voices from another room. All of these various white noises tell us where we are, registering at the back of our minds and then fading beneath the actions of the plot and the words of the dialogue. They keep us in the space, our disbelief suspended. The scraping of a chair, the sound of a car outside, someone answering a phone call in the lobby — these things drop us back into reality, reminding us that we’re sitting in a theatre in Toronto in 2016, not on a French shore in 1943, or on a castle wall in medieval Denmark, or in a warm Freudian womb.

A sound designer would have watched a rehearsal of this show and come back with a two hour soundtrack of the various white noises required for each scene. They would have shaped the audience’s expectations and experiences from the moment they walked into the space with a carefully chosen pre-show playlist, had them discussing among themselves at intermission with further music, and leaving in the right frame of mind at the end with post-show sounds. They would have masked the creaks and groans of the building, the footsteps of actors, the shuffles of coats, and replaced them with gentle sounds that creep in at the edge of your awareness and are then accepted by the mind and mostly forgotten — but not quite. They would have wrapped the show in a blanket; sometimes comforting, sometimes scratchy, but always enclosing the space and the dream of the play, and keeping the monsters of reality at bay.

When designers and technicians do their jobs right, you rarely notice that they did much at all. But you can feel it — or the absence of it — like a joy, or like a weight, or like a blanket of emotions. Not having a designer is like going to the seaside on a day when the water is perfectly, eerily calm, and having your brain cry out for the lack of waves.

I happen to come from a school of design that was all-encompassing in its scope. When I design shows, I think not just about how it looks and how it sounds, but how it feels, and tastes, and smells. What is the temperature in the room? How do the seats feel? Is there a scent to the building (and do we want to bring in air fresheners, or pine shavings, or dryer sheets, or stale beer?). Should we have fans blowing air across the audience’s faces? I want people to move through the lobby in specific ways, and see things on the way to their seats. I want to serve snacks so that they all have salt in their mouths and feel the thirst of the characters. I consider where the theatre is — what city, what street? Who lives here? What will the audience have passed on their way to the theatre? What experiences will have shaped their landing here, in these seats, and how can I harness that? That is the designer’s job. The playwright gives you the words. The director gives you the movements. The producer gives you the audience, and the actors give you the raw materials. But the designers give you the space and time and world for all of that to live and play within.

The denizens of that world, then, thank you in advance for always hiring designers, and not falling into the trap of thinking that you can do it yourself. Because while you might know very well what you want, it’s unlikely that you’ve thought of all the other stuff that’s going to muck it up.

with all appropriate credit to Steve Younkins at http://q2qcomics.com

Please, for the love of all the theatre gods, hire designers.