“Hey, I like your hair!”

I was halfway through opening my mouth to say a quick “thanx” , when the second half of the statement hit me like a slap across the face:

“But you dropped your smile!”

Now, as a young female-bodied person in a city like Toronto, I’m no stranger to street harassment. It’s rare that I can be out walking, shopping, etc. for more than a few minutes without someone shouting a catcall or honking a horn or making an unsolicited comment on my appearance. And most of it rolls right off my back — in the 5 years I’ve been living in this city, I’ve developed a thousand-mile stare, resting bitch face, and a purposeful stride when walking anywhere. I’ve learned to put up the armor, to keep going and ignore, to be ready to run or to fight if they pursue me. I’ve learned how to identify which people are just harmlessly creepy, and which are more likely to be genuine threats: the kind that reach in for a grope, or start following you when you don’t respond to their advances.

This particular time, though, I was truly caught off-guard. I was in a neighborhood where I generally feel fairly “safe” — Church and Wellesley, right in the middle of the gay village, where the street harassment that I witness is usually male-on-male (and yeah, it’s uncomfortable, but at least it’s not directed at me). The person talking at me was female. And she was carrying a binder. She was out campaigning for pledges for Plan Canada’s “Because I am a Girl” campaign, and that was what stopped me dead in my tracks, mouth open, not even knowing how to begin to respond. I actually took a few steps away before turning around and confronting her.

“No, you know what? You don’t get to say that to me. That is fucking sexist, and it is bullshit. You don’t own my body”. She stammered a protest, tried to claim that she hadn’t said anything wrong, but I was already spinning on my heel to walk away — moving faster, bitch-face firmly in place, practically fuming that an ostensibly feminist organization couldn’t even be bothered to give their canvassers some simple sensitivity training about how to correctly approach a person cold.

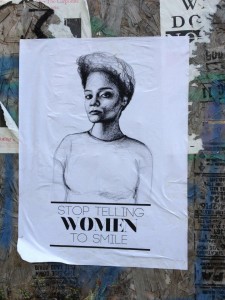

Why You Should Never Tell a Person — Especially a Female-Bodied Person — to Smile

What it comes down to, mostly, is the simple fact that a stranger does not owe you anything. If they’re a service-industry person and you’re their customer, fine, they might be expected to appear pleasant and pleasing to you (and you might be justified in knocking a percentage or two off the tip for surly, unsmiling service). Human resources might back you up when you complain about that coworker who’s never happy. And if a friend or family member is looking unsmiling and dour, you’re probably justified in asking them what’s going on. But with a stranger?

You don’t know what their day has been like. You don’t know what’s on their mind. Maybe they just got dumped, their dog just died, they’ve got a major deadline coming up at work and are stressed and overtired — or maybe some other asshole just said something awful to them not ten seconds ago. Maybe they’re going home to a sick child, or fighting to keep from being evicted, or running late, or they just threw their seven-dollar latte in the trash because the barista screwed up and made it with soy milk. Or maybe, just maybe, the expression on their face has to do with absolutely anything in the world that isn’t you. Maybe they’re lost in thought, and it isn’t a frown, just a pensive non-smile. Or maybe they’ve been warned not to smile at strangers (especially strange men), because then they might be thought to be “asking for it” (whatever “it” is).

Women, especially, spend a lot of our time being told (by the media, by peers, etc), that our bodies are not our own. Ongoing debates about topics such as abortion, the definition of “rape” (especially as it pertains to “marital rape” and “coercive rape”), access to contraception, etc., frame women’s bodies as something of a sociopolitical object, not a person. Puritanical attitudes towards sex place women as “gatekeepers” of sexual and sensual pleasure, foisting the responsibility for others’ misbehaviour onto us in a sort of paternalistic “well you should have known better” and “boys will be boys” shrugging-off of the realities of the world. And yet, simultaneously, we are expected to be miraculously young-and-beautiful (via cosmetics, surgeries, whatever), eternally thin, eternally sexually appealing, because to not conform to society’s standards of feminine beauty is to appear “slovenly” and “uncaring” and “unprofessional”. Displays of negative emotion are seen as either weak or threatening (or sometimes both), and yet being stoic and self-contained is “unnatural” or unfeminine (and, again, may well be taken as a threat). Every decision that we take with our appearance is a catch-22 of some sort, and will likely be questioned and criticized by many people.

So when you tell a female-bodied person to “smile, sweetheart”, or that her face would look better with a smile on it, or that she shouldn’t forget her smile, or whatever else — you’re playing in to that patriarchal concept that women’s bodies are not our own, but rather public property, useful only to please others. Telling anyone to smile for you is entitled, but cultural context makes this even more true when that person is a woman.

Why it is Threatening (and what you should do about that)

Of course, the reasons why street harassment is shitty don’t end with simple objectification and entitlement. There’s the threat element, too. Not every instance of street harassment is a red-alert, fight-or-flight sort of situation — in the case of the stupid Church Street girl with her binder and her lack of training, I certainly didn’t feel like I was in any danger. It was daylight, a busy street, a relatively safe neighborhood, and she was just one person, not much taller than me. It was unlikely in the extreme that she was carrying a concealed weapon, or going to jump me when I turned my back. But the majority of street harassment isn’t quite so benign. It only takes one instance of getting groped on the subway, or followed home late at night, or having objects thrown at you, to plant the seed of fear & have you questioning your safety every time someone makes eye contact or steps into your personal bubble. And we spend a lot of time getting warned to not get ourselves raped — whenever an attack is in the news, a woman is questioned for what she was wearing, why she was alone, why she was in that neighborhood, why she didn’t call for help or fight harder to escape or have the presence of mind to have not been born with a vagina. So we are constantly questioning, constantly worrying, wondering if letting our guard down for even a moment will be the time that we made a mistake & get assaulted or raped or killed as a consequence.

And it really doesn’t matter that 99% of the time, it isn’t a threat. The vast majority of the time, the person approaching you with a leer or a whistle or an unsolicited comment or a demand for a smile is going to just walk away (perhaps after hurling an insult at you for daring to snub their advances — “stuck up bitch”, or “fuck you, you’re ugly anyway”, or something of that ilk is fairly common). Those few times when it IS a threat, we need to be on guard and ready to act — to run, to scream, to fight, whatever is necessary to protect ourselves, because if we don’t put up enough of a fight, the law won’t defend us nor punish our attackers. If we’re not ready to claw the fucker’s eyes out while screaming RAPE at the top of our lungs, we were clearly “asking for it”, and it wasn’t “legitimate rape“.

This is all, of course, a symptom of a much larger problem –again, cultural context means everything. If victims were better protected by the legal system, we wouldn’t have to rely so much on our own physical ability to defend ourselves. If criminals were punished more effectively, there would be fewer willing to commit the crimes in the first place. And if people were taught to not commit rape, instead of being taught to not GET raped, we might have different social norms to work with, here. But until we see wide, systemic change, every approach must be treated as a threat — because if it isn’t, you were “asking for it”.

Hollaback

There’s been quite a bit of attention paid, in recent years, to the Hollaback movement. Basically, it encourages victims and witnesses of street harassment to do exactly what I did: call them out on it.

While I think that the general idea has some merit, it’s not really the solution. As anyone who experiences regular street harassment can tell you, engaging them usually only serves to make it worse. People are, as a rule, usually unwilling to admit wrongdoing, even when directly confronted. They’re more likely to react with aggression to what they perceive as an attack on them. So in many cases (the already threatening cases, as outlined above), being able to “hollaback” at someone who has just threatened you takes real courage, and a willingness to fight or run like hell should things go south.

And Hollaback does, unfortunately, put too much onus on the victim to save themselves. While the campaign encourages people who are merely witnesses or bystanders to speak up as well, it is largely aimed at the people (women, people of colour, and other visible minorities) who are already being oppressed and attacked. It’s an imperfect, band-aid solution at best. Worth drawing attention to, though, because in cases where it IS safe to do so, calling people out (whether in the moment, or after the fact via means such as social media, blogging about it, postering areas where street harassment habitually occurs, etc) draws attention to the issue and hopefully encourages & supports other who are experiencing the same sort of attacks.

Of course, as critical as I am of Hollaback’s effectiveness, I’m not sure if we have any better solutions right now.

Social change is a long, convoluted, difficult, painful process. I don’t really expect that I will ever, in my lifetime, see a world where women in densely populated urban areas are truly free to go about our days. But I do hope that it will get at least a little bit better. Getting street harassed by a supposedly-feminist canvasser was a pretty low point, I think, and the world needs, absolutely NEEDS, to be better than this.

For the moment, pleasant fantasies will have to do.

Bane. Bane was going to be a tough villain to sell effectively, no matter how you look at it. The combination of genius intellect and violent thuggery that the character represents provides numerous challenges to writer, director and actor, who must find ways of reconciling the seeming inconsistencies of Bane’s character. Many incarnations of Bane have failed at this — the most obvious being the “Batman & Robin” version of the 90s, which reduced the character to a voiceless, brainless minion. Tom Hardy’s imagining of the character does better than this, but he’s unimaginably hampered by the directorial/writing choices that have been set against him, with the result being a lackluster performance that just doesn’t resonate on any level.

Bane. Bane was going to be a tough villain to sell effectively, no matter how you look at it. The combination of genius intellect and violent thuggery that the character represents provides numerous challenges to writer, director and actor, who must find ways of reconciling the seeming inconsistencies of Bane’s character. Many incarnations of Bane have failed at this — the most obvious being the “Batman & Robin” version of the 90s, which reduced the character to a voiceless, brainless minion. Tom Hardy’s imagining of the character does better than this, but he’s unimaginably hampered by the directorial/writing choices that have been set against him, with the result being a lackluster performance that just doesn’t resonate on any level.

A large part of why I didn’t hate the film was, of course, Anne Hathaway’s portrayal of Selina Kyle (Catwoman). Going in, I wasn’t sure if she was the right casting for the role (I mean really, the girl from “The Princess Diaries” as a femme fatale? Would it work?) — and I was very much pleased to be proven wrong in my doubts. Hathaway brings a sweetness (I won’t say “innocence”, since Selina Kyle is certainly no innocent) to the character that hasn’t really been there since Julie Newmar played her in the 60s. That sexy little “oops” she delivers when caught by Bruce in the manor’s safe? The matter-of-fact way in which she states things (standing in sharp contrast to the melodramatic deliveries given by many of the male leads)? The relationship with Holly (beautifully vague — love it!) … all of it lends her a great depth. Even the way that she moves and breathes seems properly Catwoman-esque. And while I’m usually not a fan of women’s costumes in action movies (for all the usual feminist reasons), I do like the costume — it’s suitably sexy, without being gratuitous (it shows very little skin, and is really quite a functional garment, despite the heavy Dominatrix look), and I like the fact that traditional female comic book costume is poked fun at when another character asks about her high heels, and she promptly kicks him with them (the heels are serrated steel, by the way, and deal some pretty nasty puncture wounds). These are not “fuck me” heels, they are “fuck you” heels, and I (as a wearer of ridiculously high heels myself) love that. The character was, of course, undermined by the film’s tired Hollywood tropes — coming back to save the hero, just like she said she wouldn’t, and then that awful little scene at the end with her and Bruce in the cafe — but overall she manages to stand as a realistic, sympathetic, and strong female role, which was certainly quite a challenge. I’d expected them to go the tired old “prostitute with a heart of gold” route, and seeing her as a flawed and realistic human being was lovely.

A large part of why I didn’t hate the film was, of course, Anne Hathaway’s portrayal of Selina Kyle (Catwoman). Going in, I wasn’t sure if she was the right casting for the role (I mean really, the girl from “The Princess Diaries” as a femme fatale? Would it work?) — and I was very much pleased to be proven wrong in my doubts. Hathaway brings a sweetness (I won’t say “innocence”, since Selina Kyle is certainly no innocent) to the character that hasn’t really been there since Julie Newmar played her in the 60s. That sexy little “oops” she delivers when caught by Bruce in the manor’s safe? The matter-of-fact way in which she states things (standing in sharp contrast to the melodramatic deliveries given by many of the male leads)? The relationship with Holly (beautifully vague — love it!) … all of it lends her a great depth. Even the way that she moves and breathes seems properly Catwoman-esque. And while I’m usually not a fan of women’s costumes in action movies (for all the usual feminist reasons), I do like the costume — it’s suitably sexy, without being gratuitous (it shows very little skin, and is really quite a functional garment, despite the heavy Dominatrix look), and I like the fact that traditional female comic book costume is poked fun at when another character asks about her high heels, and she promptly kicks him with them (the heels are serrated steel, by the way, and deal some pretty nasty puncture wounds). These are not “fuck me” heels, they are “fuck you” heels, and I (as a wearer of ridiculously high heels myself) love that. The character was, of course, undermined by the film’s tired Hollywood tropes — coming back to save the hero, just like she said she wouldn’t, and then that awful little scene at the end with her and Bruce in the cafe — but overall she manages to stand as a realistic, sympathetic, and strong female role, which was certainly quite a challenge. I’d expected them to go the tired old “prostitute with a heart of gold” route, and seeing her as a flawed and realistic human being was lovely.