I’m trying to get back into the habit of blogging a bit more regularly, so in that interest, here’s a more lighthearted post than I am sometimes wont to share: Coffee! A bit about the history, science, and serving of one of my favourite beverages.

The History

According to the International Coffee Organization, coffee trees first originated in the Ethiopian region of Kaffa, where the “coffee cherries” (as the beans were called) were eaten by slaves. The name “Kaffa” means “drink made from berries”, so it’s obvious that coffee was an important regional drink. Once the beverage started to become known & spread through the Arab world (originally as a part of religious ceremonies, then later entering secular culture), their traders tried to gain a monopoly by imposing strict bans on the trading of fertile beans, but this couldn’t last forever: in the early 17th century the Dutch brought live plants to India and Java for cultivation (although an alternate story has an Arabic holy man strapping fertile beans to his chest and smuggling them to India, which I must admit is a more romantic tale), and the coffee plant began to spread worldwide. One particularly interesting story is that of how coffee came to the island of Martinique:

In 1720 a French naval officer named Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, while on leave in Paris from his post in Martinique, acquired a coffee tree with the intention of taking it with him on the return voyage. With the plant secured in a glass case on deck to keep it warm and prevent damage from salt water, the journey proved eventful. As recorded in de Clieu’s own journal, the ship was threatened by Tunisian pirates. There was a violent storm, during which the plant had to be tied down. A jealous fellow officer tried to sabotage the plant, resulting in a branch being torn off. When the ship was becalmed and drinking water rationed, De Clieu ensured the plant’s survival by giving it most of his precious water. Finally, the ship arrived in Martinique and the coffee tree was re-planted at Preebear. It grew, and multiplied, and by 1726 the first harvest was ready. It is recorded that, by 1777, there were between 18 and 19 million coffee trees on Martinique, and the model for a new cash crop that could be grown in the New World was in place.– International Coffee Organization

In Europe during the 17th century, coffee was widely believed to have medicinal properties (not entirely untrue, since coffee has been shown in various studies to prevent Parkinson’s disease, type 2 diabetes, and liver diseases, as well as decreasing the risk of depression), and it quickly became a part of the mainstream. Coffee houses soon became a place for political groups to gather & discuss their plans (most famously, the Boston Tea Party was planned in a coffee house in 1773), and many coffee houses evolved into major financial institutions (including Lloyds of London, the New York Stock Exchange, and the Bank of New York).

In 1884, an important innovation in coffee technology came along: Angelo Moriondo’s steam-driven instantaneous coffee-making machine (patent no. 33/256). In 1902, Luigi Bezzera patented his improvements to the device, and then in 1905, the patent was purchased by Desiderio Pavoni, who began to produce the world’s first commercially available espresso machines. The espresso machine was further refined in 1932 by Achille Gaggia, whose higher-pressure models produced what we would recognize as espresso today: thick, syrupy coffee topped with a golden foam that Gaggia dubbed “caffe crema”. The first Faema machine, introduced in the 60s, replaced the manual power required to pull a shot from the Gaggia machines with a motorized pump, but otherwise espresso has remained largely unchanged since WWII.

Types of Coffee Makers

The way your coffee tastes depends largely on the way it is made, and to that end there are a variety of different coffee brewing methods available. Each method has its benefits and downsides, and of course each camp has its vehement defenders.

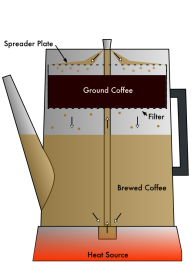

Probably the most familiar (to a North American, anyway) is the inexpensive drip coffee maker. There are a few variations available — basket vs. cone filters, glass vs. thermal carafes, and of course there are all the added features like clocks, timers, radios, automatic shut-off, etc. Most of us grew up with one of these in our kitchens, and the gurgle-sputter noise as the last drips finish brewing is a friendly, homey, nostalgic sort of sound.

Probably the most familiar (to a North American, anyway) is the inexpensive drip coffee maker. There are a few variations available — basket vs. cone filters, glass vs. thermal carafes, and of course there are all the added features like clocks, timers, radios, automatic shut-off, etc. Most of us grew up with one of these in our kitchens, and the gurgle-sputter noise as the last drips finish brewing is a friendly, homey, nostalgic sort of sound.

Drip coffee is unquestionably the simplest to make. No worries about timing, or even careful measuring — just scoop out a few heaping tablespoons of ground coffee into the filter, pour in water, and turn on. A few minutes later, you’ll have fresh coffee — no fuss, no muss. And most machines will turn off all by themselves, so you don’t need to worry about whether you forgot to hit the button — some even turn on by themselves, only needing to have the timer set the night before so that you can wake up to pre-made coffee before your early morning shift. Drip coffee is also the most convenient for serving a crowd — easily make enough for the whole family all at once, without having to stand there monitoring it. Unfortunately, drip coffee is also the least flavourful method — the water in these machines doesn’t get as hot as when brewing by other methods, and thus less flavour is pulled out of the beans. You can improve the flavour you get by purchasing better quality whole beans & grinding them fresh each day, but this does somewhat defeat the “easy & no fuss” factor that makes drip machines appealing in the first place.

Espresso machines (mentioned earlier in the “history” section) are at the opposite end of the spectrum, in many regards. Expensive — a good one can easily set you back a thousand dollars — and fussy — the temperature and pressure need to be adjusted to account for humidity and barometric pressure on a regular basis in order to maintain quality — espresso drinks are something that many people leave to the professional baristas at their favourite coffee shop. But all of that fuss means a lot more control over your final cup of coffee, and in a house with coffee drinkers who have widely varying tastes, this can be a big plus, because each person can prepare their individual coffee to their individual liking. Espresso machines are also useful when you have just one or two coffee drinkers, and don’t want to make & waste full pots.

Espresso machines (mentioned earlier in the “history” section) are at the opposite end of the spectrum, in many regards. Expensive — a good one can easily set you back a thousand dollars — and fussy — the temperature and pressure need to be adjusted to account for humidity and barometric pressure on a regular basis in order to maintain quality — espresso drinks are something that many people leave to the professional baristas at their favourite coffee shop. But all of that fuss means a lot more control over your final cup of coffee, and in a house with coffee drinkers who have widely varying tastes, this can be a big plus, because each person can prepare their individual coffee to their individual liking. Espresso machines are also useful when you have just one or two coffee drinkers, and don’t want to make & waste full pots.

Just like with drip coffee, you can use absolutely any beans in an espresso machine, but lower quality beans will show more starkly: espresso machines, with their high pressures, actually emulsify the oils in the coffee beans, so older or cheaper beans will result in very bitter espresso. Most espresso machines come with a “steam wand” attachment so that you can easily prepare beverages such as lattes and cappuccinos by steaming the milk, which greatly expands the usefulness of this counter-space hog.

The stovetop espresso pot, or “Moka Pot” as they are commonly known, brews an espresso-like coffee under less pressure (usually about 2 bars), thus emulsifying less of the oils and producing less “crema”. It is not actually a “true” espresso, which is defined by the 9 bars of pressure used in standard machines, but it tastes similarly & can be used for making a delicious latte, americano, or cafe-au-lait. Moka Pots are actually one of my personal favourite home-brewing methods, as they are great for making coffee for only one or two people (although you can get larger pots designed for making up to 6 cups at a time), and result in a stronger, richer flavour than you get with a drip coffee maker, without the sediment problems of French press coffee (see below). It tastes very similarly to coffee made in a percolator, without the risk of over-extracting the beans by recirculating the coffee through them. Moka Pots are often confused with percolators by people who are not familiar with them.

The stovetop espresso pot, or “Moka Pot” as they are commonly known, brews an espresso-like coffee under less pressure (usually about 2 bars), thus emulsifying less of the oils and producing less “crema”. It is not actually a “true” espresso, which is defined by the 9 bars of pressure used in standard machines, but it tastes similarly & can be used for making a delicious latte, americano, or cafe-au-lait. Moka Pots are actually one of my personal favourite home-brewing methods, as they are great for making coffee for only one or two people (although you can get larger pots designed for making up to 6 cups at a time), and result in a stronger, richer flavour than you get with a drip coffee maker, without the sediment problems of French press coffee (see below). It tastes very similarly to coffee made in a percolator, without the risk of over-extracting the beans by recirculating the coffee through them. Moka Pots are often confused with percolators by people who are not familiar with them.

Percolators are distinct from stovetop pots because there is not a separate chamber for the coffee after brewing — it simply drips back down into the main body, where water was poured in at first. Percolators have gone out of fashion since the advent of the drip coffee maker, but were once the worldwide standard for brewing — and they are fairly simple, as long as you keep an eye on the time. They do tend to make better tasting coffee than drip coffee makers as long as you don’t over-extract the beans by leaving it on the heat for too long (which results in bitterness), because the water can get to a higher temperature, allowing for more flavour extraction. Unfortunately, their drop in popularity has meant that finding filters for them is almost impossible — percolator purists tend to have to buy online (although there are some “permanent filters” available these days, which can mitigate that problem). People who enjoy camping often swear by perk coffee (and incidentally, the percolator is where the phrase “the coffee is perking” comes from), because it’s easily prepared over an open fire or on a camp stove.

Percolators are distinct from stovetop pots because there is not a separate chamber for the coffee after brewing — it simply drips back down into the main body, where water was poured in at first. Percolators have gone out of fashion since the advent of the drip coffee maker, but were once the worldwide standard for brewing — and they are fairly simple, as long as you keep an eye on the time. They do tend to make better tasting coffee than drip coffee makers as long as you don’t over-extract the beans by leaving it on the heat for too long (which results in bitterness), because the water can get to a higher temperature, allowing for more flavour extraction. Unfortunately, their drop in popularity has meant that finding filters for them is almost impossible — percolator purists tend to have to buy online (although there are some “permanent filters” available these days, which can mitigate that problem). People who enjoy camping often swear by perk coffee (and incidentally, the percolator is where the phrase “the coffee is perking” comes from), because it’s easily prepared over an open fire or on a camp stove.

The French Press has seen a surge in popularity recently, especially among singles and apartment-dwellers (like the Moka Pot, it takes up very little in the way of counter space, and doesn’t require a devoted outlet). Devotees of the French Press declare that the slower brewing method produces a fuller flavour, but I personally tend to find it bitter. There is also a distinct likelihood that French Press coffee will have large chunks of coffee grounds still floating in it after filtering, which is what really turned me away from the method — I don’t like grit in my teeth after drinking.

The French Press has seen a surge in popularity recently, especially among singles and apartment-dwellers (like the Moka Pot, it takes up very little in the way of counter space, and doesn’t require a devoted outlet). Devotees of the French Press declare that the slower brewing method produces a fuller flavour, but I personally tend to find it bitter. There is also a distinct likelihood that French Press coffee will have large chunks of coffee grounds still floating in it after filtering, which is what really turned me away from the method — I don’t like grit in my teeth after drinking.

The French Press is an old-fashioned and simple method of brewing, and highly portable, so its popularity makes sense. Like with percolators, you do need to keep an eye on the time — the longer you brew, the more likely those bitter flavours will come out, so you have to find the right balancing point for your taste buds. High quality, freshly ground beans will also mitigate the bitter-factor.

A new innovation in home coffee brewing technology is the single-cup brewer, popularized by brands like Keurig and Tassimo. Also popular among the singles-and-apartment-dwellers crowd, these machines are quite versatile, but also represent the most expensive method of getting your daily caffeine-fix short of actually going to a coffee shop and paying someone else to do it. Many of the brand-specific “k-cups” and “pods” can run well over a dollar apiece, and then there’s also the start-up cost (usually several hundred dollars) to be considered. Most of the “pods” available are low-quality coffee brands, too, so you’re not getting the best tasting coffee, even if it’s costing you the most money. They’re ridiculously simple, though: just pop in a pod and whatever drink you wanted magically appears in your cup, just for you. And with the advent of refillable, reusable “pods” that you can fill with whatever type of coffee you like, the cost can be brought down with a little effort. I’ll admit to having enjoyed the novelty of them when staying at hotels or working in buildings where there was a single-cup brewer available for use. And some of the smaller ones are quite portable — a woman I work with brings her little Tassimo brewer to work with her, even when we’re on set, so that she can always have fresh coffee. But to be honest, if I was going to spend that kind of money on home-brewed coffee, I’d get a proper espresso machine and skip all the single-cup nonsense.

A new innovation in home coffee brewing technology is the single-cup brewer, popularized by brands like Keurig and Tassimo. Also popular among the singles-and-apartment-dwellers crowd, these machines are quite versatile, but also represent the most expensive method of getting your daily caffeine-fix short of actually going to a coffee shop and paying someone else to do it. Many of the brand-specific “k-cups” and “pods” can run well over a dollar apiece, and then there’s also the start-up cost (usually several hundred dollars) to be considered. Most of the “pods” available are low-quality coffee brands, too, so you’re not getting the best tasting coffee, even if it’s costing you the most money. They’re ridiculously simple, though: just pop in a pod and whatever drink you wanted magically appears in your cup, just for you. And with the advent of refillable, reusable “pods” that you can fill with whatever type of coffee you like, the cost can be brought down with a little effort. I’ll admit to having enjoyed the novelty of them when staying at hotels or working in buildings where there was a single-cup brewer available for use. And some of the smaller ones are quite portable — a woman I work with brings her little Tassimo brewer to work with her, even when we’re on set, so that she can always have fresh coffee. But to be honest, if I was going to spend that kind of money on home-brewed coffee, I’d get a proper espresso machine and skip all the single-cup nonsense.

While there are dozens of other little “niche” methods of making coffee (one of the coffee shops that I regularly frequent has a whole mad-science laboratory full of contraptions for roasting, grinding & brewing), the only other one that I think is necessary to mention here is cold-brewing (follow the link for more detail). Perfect for making iced coffee beverages in the summer (or, let’s face it, any time of year at all, because iced coffee is delicious), cold-brewing produces an incredibly smooth-flavoured coffee with very little bitterness or acid. You can get whole fancy contraptions for doing it (the “Toddy” system is very popular & works well; we used it at a coffee shop where I used to work), but all that’s really needed is 2 mason jars, a large funnel, and a filter (just buy a box of the cone-filters designed for drip coffee makers, or use cheesecloth). In one mason jar, put coarse-ground coffee beans & cold water. Leave it in the fridge for 12 hours, then pour through the funnel (using the filter to strain out the grounds) into the second mason jar. Pop the lid on and you’ve got cold-brewed coffee to last you for the whole week. Getting the exact amount of coffee beans, the grind, and the amount of time correct can take a bit of trial-and-error, but it’s an experiment worth doing if you enjoy iced coffee drinks. Never again will you just pour hot coffee over ice, watering it down & resulting in high-acid bitterness.

While there are dozens of other little “niche” methods of making coffee (one of the coffee shops that I regularly frequent has a whole mad-science laboratory full of contraptions for roasting, grinding & brewing), the only other one that I think is necessary to mention here is cold-brewing (follow the link for more detail). Perfect for making iced coffee beverages in the summer (or, let’s face it, any time of year at all, because iced coffee is delicious), cold-brewing produces an incredibly smooth-flavoured coffee with very little bitterness or acid. You can get whole fancy contraptions for doing it (the “Toddy” system is very popular & works well; we used it at a coffee shop where I used to work), but all that’s really needed is 2 mason jars, a large funnel, and a filter (just buy a box of the cone-filters designed for drip coffee makers, or use cheesecloth). In one mason jar, put coarse-ground coffee beans & cold water. Leave it in the fridge for 12 hours, then pour through the funnel (using the filter to strain out the grounds) into the second mason jar. Pop the lid on and you’ve got cold-brewed coffee to last you for the whole week. Getting the exact amount of coffee beans, the grind, and the amount of time correct can take a bit of trial-and-error, but it’s an experiment worth doing if you enjoy iced coffee drinks. Never again will you just pour hot coffee over ice, watering it down & resulting in high-acid bitterness.

Cappuccino, Latte, Cafe-au-Lait? Whaa?

When I had a part-time job as a barista, this was one of the questions that got asked literally every day, so I’ll go through a few of the most common coffee and espresso beverages that you’ll see on the menus at various cafes. There might be a few on here you’ve never heard of — feel free to try to stump your local barista with an offbeat one, but remember to tip well for the inconvenience.

Cafe Americano (or just “americano” to many) is a shot of espresso, topped up with hot water to “lengthen” it. The story goes that American soldiers in Italy during WWII found that they couldn’t find the perk coffee they were accustomed to, because espresso machines had exploded on to the scene. They didn’t enjoy the thick, strong, tiny drinks that were so popular, and would dilute them with water to closer approximate the coffee they knew and loved. Americano coffee has a different flavour from your standard drip or perk coffee, due to the different extraction method, and many people prefer it for that reason.

A Long Black is virtually identical to an americano, but instead of adding the water to the espresso, you add the espresso to the water. Purists claim that this maintains more of the espresso’s natural “crema”, and there is a slight visual difference, but I can’t say that it alters the flavour (to my tastes, anyway).

The Red Eye (also known as the “shot in the dark”) is a single shot of espresso added to a cup of dark roast coffee — the point being to increase the boldness, flavour, and caffeine content of the drip coffee. If you want to add 2 shots instead of just one, it’s called a Black Eye, and 3 shots is a Green Eye.

Cappuccino is a shot of espresso topped with hot steamed milk & foam. Traditionally, you want about equal amounts of milk & foam (the ideal cappuccino is 1/3 espresso, 1/3 milk, 1/3 foam), but you can ask for your cappuccino “wet” (more milk) or “dry” (more foam) to adjust the flavour, or have extra shots of espresso added for boldness. The foam on any espresso drink should be made up of very tiny bubbles (commonly called “microfoam”), visually resembling the medium-density upholstery foam you might find in a couch cushion. Big bubbles are a sign of an inexperienced or lazy barista.

Latte is very similar to cappuccino, but uses almost all hot milk, with just a little bit of foam at the very top. Because there is more milk, lattes are less strong in flavour than a cappuccino — and they’re also ideal for adding extra flavours to (ie. vanilla, hazelnut, pumpkin spice, etc). A mocha latte (or just “mocha”) is a latte made with chocolate. Lattes are often scoffed at by coffee purists as a drink for people who lack taste, but hey, sometimes we all just want something sweet & simple.

Chai lattes or tea lattes are not made with espresso, but rather with very strong tea (or in some cases, a boxed tea concentrate — most mainstream chains like Starbucks will use something from a box or bottle in order to maintain consistent flavour from shop to shop). These boxed concentrates are often pre-sweetened, so be aware when ordering that you should taste it before adding sugar. Matcha lattes are made with a powdered form of green tea, and the milk will actually turn a fairly bright green (it looks kinda disgusting, but tastes delicious).

Cafe-au-lait is sometimes used to mean the same as “latte”, but actually refers to a strong dark-roast coffee (not espresso) mixed 1:1 with hot milk & no foam. Check with the barista before ordering to make sure you know what you’re getting.

Macchiato is my personal favourite espresso drink. Resembling a small cappuccino, it consists of a shot of espresso either poured into or topped with approximately an equal amount of foam. Espresso shots for macchiato are usually pulled “long” (a bit more hot water added to the shot), but the method of preparation can vary from place to place. When I make them for myself, I just pull a single shot & top with foam, no extra fuss. It should be noted that the Starbucks “caramel macchiato” drink in no way resembles what an actual macchiato is; it’s just an example of corporate marketing people taking a random Italian-sounding word and slapping it on a drink.

A flat white is 1:1 espresso and steamed milk, no foam (that’s what the “flat” refers to). They are usually served in glass cups with wire handles, for no particular reason other than “it’s traditional”. The flat white has become a very competitive art, and people who drink them regularly are often very devoted to their particular way of having it.

Caffe Leche is espresso served with sweetened condensed milk. It’s basically like drinking a coffee-caramel.

Viennese coffee (or “cafe Vienna”) is espresso topped with whipped cream (and often sprinkles or chocolate shavings).

Turkish coffee is not espresso at all, but rather coffee served in a very primitive/traditional fashion. Coffee grounds, pounded completely to dust, and sugar are put directly into water & the water is boiled to extract the coffee. The pot has to be removed from the heat as soon as it starts to boil, or the coffee will taste “burnt”, so this is a method that requires some patience and attention. There is a flair to pouring, too, so that the foam from the coffee is divided evenly between the cups. Drinking coffee with the grounds in it is a bit of an acquired taste, and can leave you with an unpleasant “gritty” feeling on your tongue if the coffee was not pounded fine enough.

A frappe is also not actually an espresso drink; it’s made with instant coffee, water, and condensed milk, and shaken until very foamy.

Espresso Cubano (or just “Cubano”) is a shot of espresso pulled directly over demarara or raw brown sugar. Put the sugar into the cup before pulling the espresso on top of it, so that the two will meld while the espresso pours.

Espresso Romano (or just “Romano”) is a shot of espresso served with a slice of fresh lemon — and it is drunk by running the lemon over the rim of the cup before you sip.

Doppio usually refers to a simple double-shot of espresso, but the name is actually derived from the double-spouted filter head used on most commercial espresso machines. In barista competitions, the doppio is the “standard” measure of espresso used in a drink.

Ristretto refers to a shot that is “restricted” — pulled for a shorter amount of time. This truncated pull results in a shot that is sweeter and has more crema than a standard single-shot or doppio.

Affogato is espresso served over a dessert — often an ice cream or pudding, but occasionally a cake. Some dessert menus at Italian restaurants will offer the option to have your dessert “affogato style”.